The Fed Cut Rates. What Does That Really Mean for Real Estate Investors?

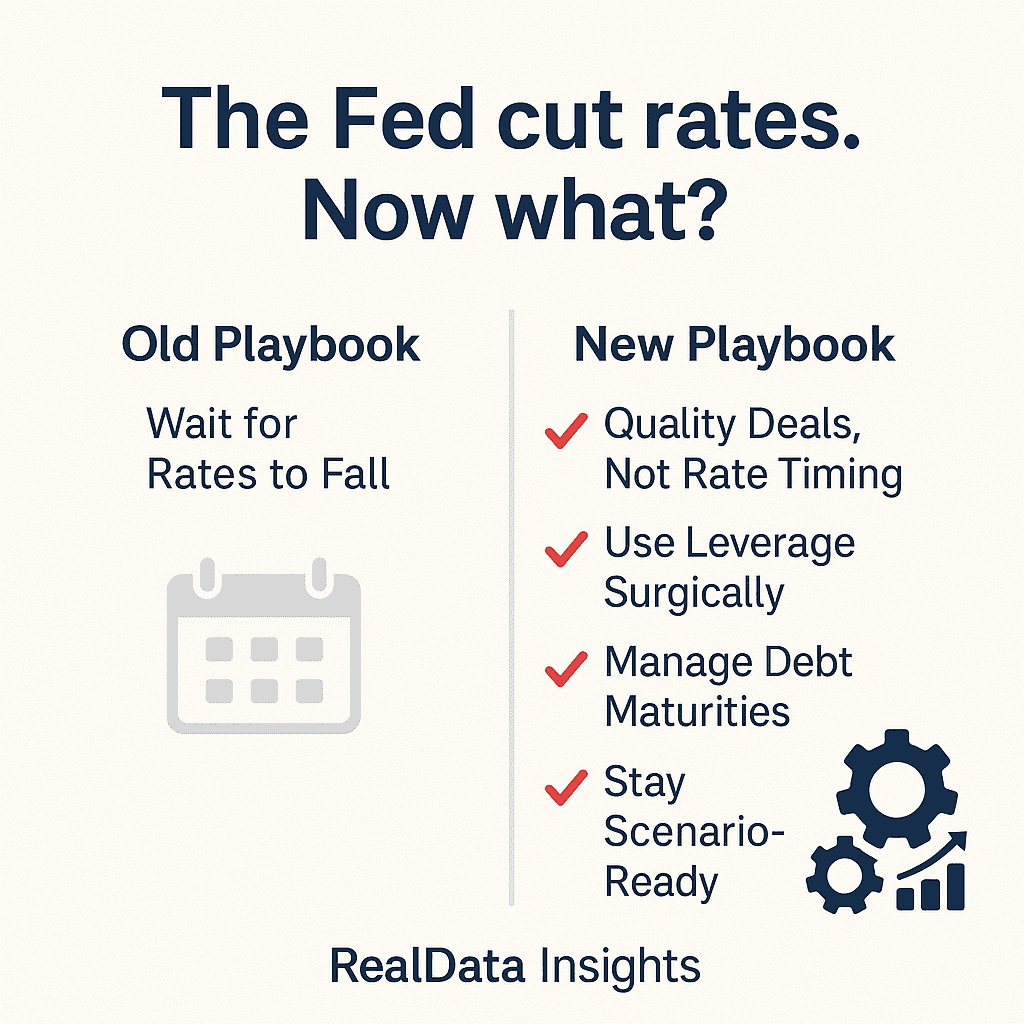

We hear all the time that users of our RealData investment analysis software are tuned in to any changes in the interest-rate envrionment.

Well… the Fed finally blinked. After two years of hikes that drove borrowing costs through the roof, the central bank cut its policy rate to 4.00%–4.25% in September. Good news, right?

disappeared. In other words: lower Fed rates don’t automatically translate into cheap financing or sky-high property values.

This is a market where “wait for rates to fall and then buy” doesn’t cut it anymore. The smart money is shifting from timing to structuring. Let’s break down what’s really happening—and how real estate investors might choose to play it.